Aditya Novali’s “Painting Sense” exhibition in Jakarta. (JG Photos/Tunggul Wirajuda)

The brushes seemed to melt into the wall, seemingly striving to overcome its limitations. One brush followed the wall’s bends and contours, giving it a striking similarity to the melting clocks in Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory.” Other brushes melded into one another through their handles or brushes at different angles and into different shapes. The brushes are among the five pieces that make up the work “Canvas Logic,” an installation art by Indonesian contemporary artist Aditya Novali. But looks can be deceiving.

“Aditya might be out to shape shift the brushes. But [‘Canvas Logic’] is actually more about form and function, instead of going into the subconscious like Surrealism would,” says Edo, the assistant curator of Aditya’s work. “Despite their looks, the items still work.”

“Canvas Logic” is one of 23 works by Aditya that’s highlighted in his work “Painting Sense.” Held at Jakarta’s ROH Projects Gallery, the exhibits sought to highlight often overlooked elements of the artist’s tools and their end products.

“Aditya presents new works that engage with the concept of painting by experimenting with essential things in the painter’s practice. In deconstructing what it means to be a painter, [Aditya] raises issues of identity and emphasizes those parts of the of the [creative] process often left marginalized and unappreciated by the observer,” says “Canvas Logic” curator Junior Tirtadji in his summary of the exhibition. “Behind simple white canvases, brushes and other tools lies a complexity of ideas and responses.”

Edo agrees with Junior.

“Aditya wants to let viewers in on his creative process and even try to make them see the art through the perspective of the brushes and other tools. He sought to reach this aim by showing the versatility of brushes and other tools in the artist’s inventory, and their important role in his work,” Edo says. “By making them into various contorted shapes, he also sought to highlight the brushes’ ability to make shapes by shape shifting it. He also explored make various shapes by interlocking the brushes.”

Aditya further explored this latter premise with “Brush Series #9” and “Brush Series #10.” Made of brushes in a triangular and crescent cut, the works show the interchangeable, almost symbiotic relations between brushes, or the brush and canvas. On the other hand, the 36-year-old sought to show viewers a piece of his mind with “Brush Logic #2.”

Seeing this imposing, oversized work leaning against a wall, it didn’t take long to see that the brush has a looming place in his psyche. On the other hand, it also shows the total devotion, and even obsession, that an artist puts into his art.

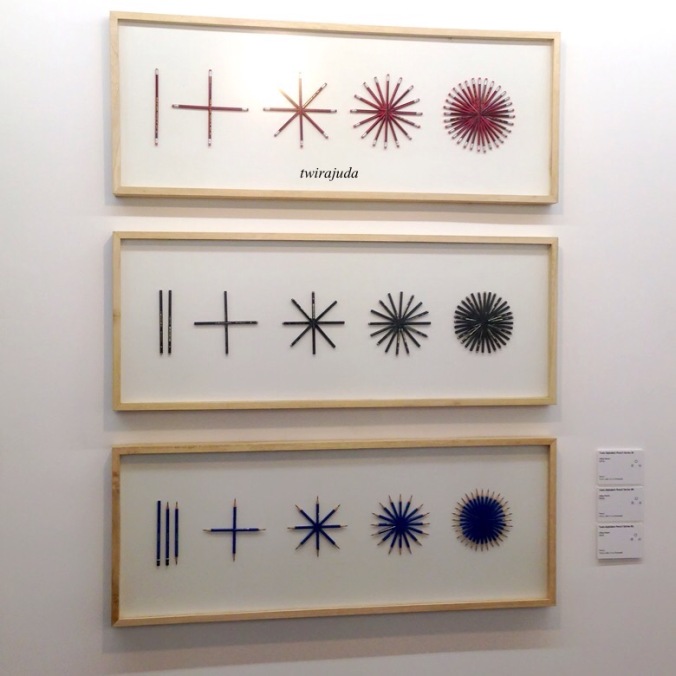

‘Behind simple white canvases, brushes and other tools lies a complexity of ideas and responses’. “Tools Alphabet — Pencil Series #1-3” (JG Photo/Tunggul Wirajuda)

Made into crosses, octagons, circles, letters and other shapes, Aditya showed in his works “Tools Alphabet — Pencil Series #1-3” and “Tools Alphabet — Paint Roller Series #1-8” that the tools not only create precision on canvas and other mediums; they can also be made artworks in their own right by turning them into three-dimensional shapes.

While the brushes in “Painting Sense” reflect Aditya’s ability to break new ground by highlighting the aesthetics of utilitarian items, they still ring true to his long-held precepts.

“[Aditya’s] works are often playful, as they have a way of combining designs in his artworks. He combines not only an exploration of paintings in his technique but also the functionality of the works,” his website adityanovali.com notes.

“Thinking as a trained designer — due to his educational background [as a Parahyangan University architecture major] — his approach to his works create a realm of playfulness, sociopolitical criticism as well as an invitation to engage the audience.”

Many of the works in “Painting Sense” share this trait along with his previous works such as “Unscale Reality” and “The End Is The Beginning,” his critique of the consumerism and materialism of urban life, or “Identifying Indonesia: The Chaos, The Process, The Contemporary,” his epic interpretation of the archipelago’s shaping in natural and sociopolitical terms. However, his canvases “Paintless Painting #1”and “Paintless Painting #2” took on a more introverted tone.

“[‘Paintless Painting #1’ and ‘Paintless Painting #2’] saw Aditya experiment with various items. These include canvas, silicone, rubber and even Betadine antibiotic salve,” Edo says. “The works are Aditya’s way to show how a painting appears in his head or subconscious, which is a far cry from the symmetry and patterns that we are accustomed to see. Its tempting to see them as similar to Rorschach tests, but they are more spontaneous and have none of the patterns that define Rorschach’s.”

The effect was striking. The broad yellowish swathes of Betadine in “Paintless Painting #1” created an effect similar to those of British Romantic J.M.W. Turner. But while the early 19th century master focused his paintings on the effect of light on nature, a trait that made him the forerunner of the Impressionist movement, Aditya seems to turn this premise inward, making him illuminate his creative process to the audience.

On the other hand, his triptych “Perfect Painting” aptly alludes to its blank state of the canvas.

Originally published in The Jakarta Globe on August 11, 2014