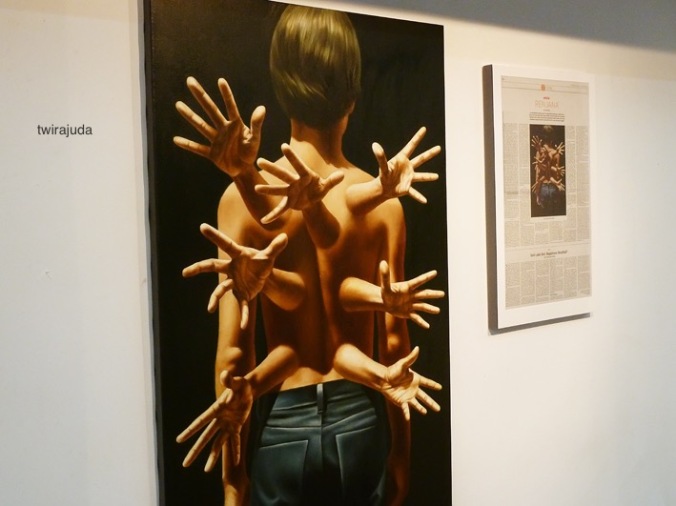

Art After Drama (Photo courtesy of Tunggul Wirajuda)

Since its invention in the late 19th century, the moving image has captivated audiences.

But the medium’s reliance on recorded images is also its primary limitation, as it often portrays fleeting external visions that are easily manipulated into a distortion of reality, according to Indonesian artist and director Krishna Murti .

This limitation is something the artist hopes to transcend and expose in “Art After Drama,” an exhibition showing at South Jakarta’s Galeri Salihara until Sunday.

“I try to show films that project the inner world of the mind. That is why many of the pieces here have a strong subconscious element,” said Krishna, who incorporates theater, film, dance and literature in his work.

“The gradual, looping formats of the video installation also explore how one’s imagination is gradually fostered. It provides a contrast between the Eastern concept of time, which is like a wheel, with the linear Western concept of time, with its chronological use of past, present and future.”

The work that best embodies Krishna’s complex expression is video installation “Eggology.”

The 12-minute looping piece, which was based on ultrasonography images of a baby in its mother’s womb, was performed by Polish theater artist Ewelina Eve Smereczynska.

Smereczynska’s flowing, fluid motions in an oval space evoke the gestures and movements of a fetus in a mother’s womb.

“ ‘Eggology’ reminds us of the need to take care of our [emotional and physical] wellbeing even before we are born. For instance, some mothers in the West do so by playing soothing classical music to their fetuses, while many Muslim mothers recite surahs , or prayers from the Koran,” Krishna said.

“Most of all, ‘Eggology’ reminds one that life begins before we come into this world. So in that sense it can represent one of many phases in life.”

“Eggology” by Krishna Murti (Photo courtesy of Tunggul Wirajuda)

Another video installation in the exhibition, “The Tale of Sangupati,” touches on Krishna’s Javanese heritage.

The monodrama, a collaboration with fellow artist Landung Simatupang, recounts the efforts of protagonist Joyo (played by Landung) to uphold the heritage of his dalang , or wayang puppeteer, ancestors.

In the piece, which features a monologue depicting Joyo’s efforts to hold on to a fading tradition, Krishna uses many symbolic details to make his point. These include wafts of cigarette smoke to show how his wayang heritage is becoming an increasingly distant memory, as well as CGI images of wayang figures forming and eventually shattering at the end of his monodrama.

“Joko is in a dilemma. On one hand, his father made him swear to maintain his family’s traditions. But on the other hand, he was forced to sell the wayang he makes, and even his own family heirlooms, to make ends meet,” Krishna explained.

“So his hardship isn’t just merely holding on to dying traditions. Metaphorically it also represents the rest of us, as we’re forced to ‘sell our souls’ just to make it in life.”

Krishna’s “Dance of the Unknown” installation presents the cycle of life as seen through TV and the Internet.

The mix of dance and video presented by Gita Kinanthi seeks to stretch the limits of reality, both literally and figuratively. It literally makes viewers strain their necks and eyes, but also conveys how film has the ability to sway public opinion and understanding.

“Usually we don’t have time to grasp the truths of what we see, because it has already been ‘provided’ for us,” Krishna explained.

Originally published in The Jakarta Globe on July 31, 2013